Agnes Pelton: Optical Illusions Create the World

I dreamt of a boat headed into a blazing sunset, but the light was only visible in the water’s reflection. The horizon was black. I woke with a sinking stomach. The dream was a language I could understand. For the past eight months my one-bedroom apartment has become raft-like, letting enough light in so the plants survive. I leave windows open deep into autumn. Lonely, I let the mold grow in corners so it might speak. And it does, in sneezes.

The last time I went to the Whitney I sang in the lobby protesting Warren Kanders’ presence on the board. He funded the museum with money made from teargas. The day before lockdown I planned to see the Agnes Pelton show, Desert Transcendentalist, there but everything tumbled over itself. To put a time stamp on the pandemic, I planned to see the show again, seven months later, before it closed. I wanted to wrap this worry and wait and sadness as the world I had known chasmed before me. I wanted to believe an illusion of control. Where was the virus during the protesting actions when I was singing, when we were dancing? It walked beside me this crisp evening in the gallery. ‘Does no one else feel the hand on their shoulder?’ I thought.

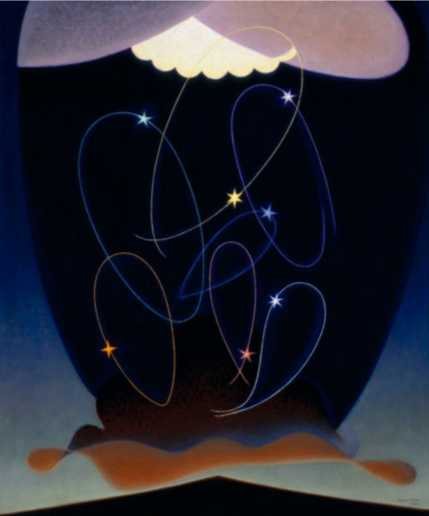

The invisible encounter was plain in the presence of the Pelton paintings. Fine, then layers of paint portray flowing, celestial, entangled, organic imagery that does not represent but transforms.

Pelton’s paintings use optical illusions to manipulate the sensation of sight. She either engages the eye by inviting it to roam along flowing threads, or creates a pulsing apparition, which manipulates the colors in the paintings. She also has a unique talent for ombre, which can feel surprising as the eye wanders into pinks that plunge into yellows, blues that become black.

I recently taught a third grader about the cones in our eyes. I had her draw a nest with a bird in it. After looking at the illustration on a white page for ten seconds, the colors morphed as we moved our eyes and the after image manifested. The greens became pink, the yellows blue. Of course, we did this exercise separately. She was hours away in a room in the country, I was in Brooklyn. Sometimes she shows me the sky from her window. I see the crosshatched screen and the sky blurry behind and I angle my computer so she can see my sky. “Is it raining where you are?” She asks.

“Yes.” I say, “it is.” We can share weather systems too.

Admittedly, the paintings lean into a new-agey aesthetic. Pelton was one of the first new-agey white women, a group that made up much of the spiritualist movement. Occasionally these women were proved to be scam artists. But they were tuned to a need, maybe even within themselves, to imagine something more than the ever speeding up global industrial systems. World War I had just occurred. I imagine Pelton also desired to change course, to imagine the life of the spirit: a virile thing, necessary to notice. Because only in the spiritual perception does the individual merge.

The paintings do something to the definition of identity. Distinct from abstract paintings providing space for anyone to assert themselves, or locate themselves within the environment of the paintings’ structure, they also diverge from the hyper individualized surrealist dream imagery. A pointed difference is in the very similar techniques of Georgia O’Keefe’s abstracted organic and geological imagery. O’Keefe worked with the same teacher, William Langston Lathrop. Pelton is both abstract and specific. She imagined the unseen, the cosmos, spirits. She represented as yet, maybe still, invisible landscapes.

On the canvas the forms have a language, implying familiar human, animal, and geological shapes, but exist as the land and a spirit entwined in one. The Fountains is a particularly striking image of a mother, a birth, and water.

Pelton’s use of color is close to hack: too optimistic, too romantic to be taken seriously. But through the near kitschiness there is bravery. To discredit kitsch is to buy into a patriarchal mindset, when it is clear Pelton was dedicated to vulvic softness. Even in her contrasting colors and concise lines the images are non-confrontational.

Within this openness the images act upon the viewer, the way an optical illusion might. She’s slips us something and our bodies don’t see, but react. When the viewer looking at the painting becomes participatory in this way they are awakened to the transformational power of light and color. But as it is the viewer is beckoned into the mush, stricken.

Pelton displaces the subject, leaving the center an orbit. She renders immense and infinitely small-scale shapes that point, in our pattern-making brains, to our own participation within those systems. Maybe Pelton’s work was considered decorative because of its lack of objectivity. She sold paintings to tourists who came to the desert. It represented, for them, a specific place, but, of course, they aren’t places. They’re actions.

I understand my apartment to be a boat, sending messages into the window of my computer screen. My window is a wall as I watch the light shift against the ruthlessly still buildings of my view.

And like the boat in my dream, we also teeter between the cosmic blackness before us, while reflections bloom with false certainty in the waters of our way. But it’s a landscape we share. Architecture and weather are forces we all live in, and they act upon us. To point to their operation is radical. Because what is invisible will send ripples into the visible. What is visible may be an illusion. And while we share so much, we can’t rely on the ghosts of others, but believe in our own experiences.

Pelton painted a white orb, not because she wanted to teach. She believed in its purpose. I am certain that beyond the heavy structures that frame the world, we share the same weather systems. Yes, it’s raining here too.

The Fountains, 1926, Agnes Pelton

Orbits, 1934, Agnes Pelton

Reflected Sunset, 2014, the writer