Future City

I hauled A Book of Signs to Printed Matter the last week in March. We orbit places. I orbit that place. But it moved from 10th Avenue to 11th, to a corner of Chelsea, further than the galleries on the west side. The store skims the river on a lonely avenue across from a BMW dealership. It makes me sad to go there. However, the decision was made years ago by someone who knew that Hudson Yards was coming and probably thought it was for the better because all the wealthy, in those steeples by the river, called Hudson Yards might think it quaint. And the poors who live on Saint Mark’s can go to the Swiss Institute. I am crying with the representational logic this stinks of. I may be wrong. I’m sorry, I love Printed Matter. I would live there if I could, but instead I creep and write about it from a distance like all the time. Because I think their soul is golden but we live in such a fucking ridiculous social and economic structure.

(#hellohudsonyards is printed all over on banners, reminiscent of the coy salutation in Hannibal)

I stumble out into Hudson Yards from tunnels of escalators layered below ground. The square does remind me of Columbus Circle as it was referred to in the New York Times recently. There is a west-facing window in the mall, like a screen or a canvas against the bustle before it. The only green space I find is a splinter of white tulips, and a huge sign with foxgloves and hydrangeas printed in soft pinks and purples against the early spring twilight to announce an arrival the words of which I don’t see. But the synthetic petals do fine in the twilight, to ease and liven the grays. The entire place is dwarfed by the soaring buildings that anchor the square’s corners. As I walk into the center the sky is webbed with the most sci-fi structure seeming to grow right out of Metropolis: the famous basket-like structure known as “Vessel,” the presence of which feels like peeking into a keyhole to a future New York. The siding is rose gold, which is a color from 2016 that still haunts my dreams. Spilling from its vortex is deep blue LED light. You need tickets to go inside, and not to be too dramatic (but it must be said), Vessel reminds me of a depiction of Dante’s 9 layers of hell as people course along its thin layers bland as ghosts from this distance.

I am surprised at how claustrophobic I actually feel in the space, considering the amount architects at Kohn Pedersen Fox were probably paid to design this. The buildings surrounding the space appear immeasurably high. I feel vertigo just looking up at them. In the center, the apex, the meager ground these buildings extend from, is the focus: the “Vessel,” which to my surprise I associate to an inverted Eiffel Tower. The structure has the same shade. I know, it might not be fair to compare the two. But the vessel asks me to. It calls to the Eiffel Tower the way the Statue of Liberty calls to her smaller sister on the Seine.

The Eiffel Tower was built for the Exposition Universelle in 1889, 130 years ago. The tower was designed by Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier in honor of the centennial of the French Revolution. The Eiffel tower rises high above the low standing Parisian buildings as a beacon. The structure itself is echoing Foucault’s panopticon, as a location for surveillance. The height represented a power over, in this case, the power of the French democracy over the people. Which can also be considered a unifier, a border maker. From the post at its tip, all the land below is theirs (think The Lion King).

When the tower was first built, a group of artists protested the structure, insisting that it was not tasteful, that it was hard and horrendous.

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of Les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years … we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.”

sourced from wikipedia

The experience of being on the Champs de Mars and walking towards the Eiffel Tower is a classical design of space. The horizontal length before the telescopic height of the Tower expands the landscape, shrinks the surrounding buildings. As if it was a king over subjects, it sparkles every night at 10pm.

The “Vessel,” unlike the structure of the French Eiffel tower is completely hidden, in a covered valley rather than a theater in-the-round. Rather than a unifier, the structure is a metaphor or a parenthesis in a city that is becoming so high it disappears into clouds.

And then there are the webs and then there are the spiders. The structures themselves are made of strands of metal as if to take the weight of it off of their hefty forms. The “Vessel” takes over the entire square between the buildings, and the small space becomes smaller, there is no distance, there is no way to extend your thumb and forefinger to hold these giant buildings. In this space we feel small, traversing an immense web, the exits of which are not visible. Perhaps we are meant to flock to the vessel, or burrow into the honey light of the mall. Because the shrinking sensation is palpable in Hudson Yards. I all but already said humans are flies in this web.

Where it’s possible to climb to the top of the Eiffel Tower one’s experience of it very personal, the tower can be fit in a pocket, seen from a distance. The bodies are not seen within it, in the presence of it, so the experience of climbing it is one of self discovery. While on the Vessel the entire interaction with it includes the others who are on it. It is impossible not to see the bodies upon it, which means immediately relationing the self to the distant bodies in the same way social media presents bodies as a form of comparison.

Inner Paris is built to frame the Eiffel Tower, and other of its landmarks just so. Let us remember the shape of Paris: Paris is often referred to as a snail, moving outwards in rings of neighborhoods. City planners, namely Hausmann reformed the city to essentially become a memorial of itself, vistas spread through the city of lights in constellations of star patterns. The Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe exist in planned views of themselves, even the beautiful Sacre Coeur, stands majestically and finally over the city like a queen, separating the city from the Banlieu. The city classified, literally moving from the inside out. The term “inner city” is not known in Paris. There is only “outer city,” this is where historically French Africans and other immigrants live. New York City seems to be taking on this strategy as well.

The word “playground” referred to in the Hudson Yards’ subway stop toys with the playgrounds that are in public parks. The vessel itself is a structure that says the city’s name as if it was a structure in a playground. Manhattan is solidifying from the inside out, gouging out old neighborhoods for huge high rises and compact, but illustrious parks. The city has not become bigger, the streets are not wider, but the use of space exists like hideouts throughout the city and the experience of walking into them is very much like stumbling from a tunnel into another plane. The highline, the Public hotel, the Williamvale in Williamsburg. These are “public parks” and yet they are so hidden, so surveilled that they crystalize standard expectations.

It’s hard to know now how Hudson Yards will integrate into the city. The geometry feels hard and unlived in. Yet people adapt. Inherently, the life in the city brings life to the buildings. It is our eyes that see the glow against the glass on the high rises at sunset, it is our bodies that know how to feel the movement of the train, it is our legs that know the feel of the escalator. When we are not used to them they feel forced. These things did once feel unnatural like breaking in a pair of shoes. Like the Eiffel Tower that may once have felt unnatural. And, honestly, it’s hard to imagine Hudson Yards including anyone who is not flying helicopters into the heli-launch on the southeastern building. Or even anyone who doesn’t have enough to buy shoes at Neiman Marcus. The people living in the city get used to a great amount of things, like how trees grow around and seep their trunks around signs, so the people who inhabit the city will learn to soar through it, the way we can grapple with Times Square. The way we marvel at The Verrazano Bridge. After 20 years the Eiffel Tower became an organ in the city’s communal body.

But there is a certain point when we know the playground is not for us. City dwellers are people who live close to one another, work close to one another, are part of a community. Whenever I have lived in a city I have not been interested in the gawking of the city so much as the shape of the land and pacing of my legs within it. Speed and tempo are important signifiers that shape the life of a place. At various points in the city’s production, the way the bodies live in the city or not decide who stays and who goes. Who is included in this sci-fi future of the Vessel?

from Metropolis

Vessel

Botticelli - Dante’s Inferno

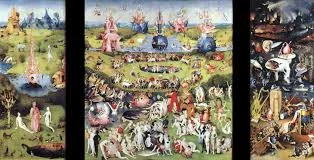

Garden of Earthly Delights Hieronymus Bosch